Armenian art has been profoundly influenced by Armenian culture, Armenia’s long history, ever-changing geography and unique mountainous landscape.

Architecture

Armenian architecture comprises architectural works with an aesthetic or historical connection to the Armenian people. It is difficult to situate this architectural style within precise geographical or chronological limits, but many of its monuments were created in the regions of historical Armenia, the Armenian Highlands. The greatest achievement of Armenian architecture is generally agreed to be its medieval churches, though there are different opinion precisely in which respects. Armenian architecture, as it originates in an earthquake-prone region, tends to be built with this hazard in mind. Armenian buildings tend to be rather low-slung and thick-walled in design. Armenia has abundant resources of stone, and relatively few forests, so stone was nearly always used throughout for large buildings. Small buildings and most residential buildings were normally constructed of lighter materials, and hardly any early examples survive, as at the abandoned medieval capital of Ani. The stone used in buildings is typically quarried all at the same location, in order to give the structure a uniform color. In cases where different color stone are used, they are often intentionally contrasted in a striped or checkerboard pattern. Powder made out of ground stone of the same type was often applied along the joints of the tuff slabs to give buildings a seamless look. Unlike the Romans or Syrians who were building at the same time, Armenians never used wood or brick when building large structures.

Armenian architecture comprises architectural works with an aesthetic or historical connection to the Armenian people. It is difficult to situate this architectural style within precise geographical or chronological limits, but many of its monuments were created in the regions of historical Armenia, the Armenian Highlands. The greatest achievement of Armenian architecture is generally agreed to be its medieval churches, though there are different opinion precisely in which respects. Armenian architecture, as it originates in an earthquake-prone region, tends to be built with this hazard in mind. Armenian buildings tend to be rather low-slung and thick-walled in design. Armenia has abundant resources of stone, and relatively few forests, so stone was nearly always used throughout for large buildings. Small buildings and most residential buildings were normally constructed of lighter materials, and hardly any early examples survive, as at the abandoned medieval capital of Ani. The stone used in buildings is typically quarried all at the same location, in order to give the structure a uniform color. In cases where different color stone are used, they are often intentionally contrasted in a striped or checkerboard pattern. Powder made out of ground stone of the same type was often applied along the joints of the tuff slabs to give buildings a seamless look. Unlike the Romans or Syrians who were building at the same time, Armenians never used wood or brick when building large structures.

Literature

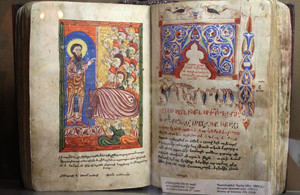

Only a handful of fragments have survived from the most ancient Armenian literary tradition preceding the Christianization of Armenia in the early 4th century due to centuries of concerted effort by the Armenian Church to eradicate the "pagan tradition". Christian Armenian literature begins about 406 with the invention of the Armenian alphabet by Mesrop for the purpose of translating Biblical books into Armenian. Isaac, the Catholicos of Armenia, formed a school of translators who were sent to Edessa, Athens, Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch, Caesarea in Cappadocia, and elsewhere, to procure codices both in Syriac and Greek and translate them. From Syriac were made the first version of the New Testament, the version of Eusebius' History and his Life of Constantine (unless this be from the original Greek), the homilies of Aphraates, the Acts of Gurias and Samuna, the works of Ephrem Syrus (partly published in four volumes by the Mechitharists of Venice). In these first years of the 5th century were composed some of the apocryphal works which, like the Discourses attributed to St. Gregory and the History of Armenia said to have come from Agathangelus, are asserted to be the works of these and other well-known men. This early period of Armenian literature also produced many original compositions. Eznik of Kolb wrote a "Refutation of the Sects", and Koryun the "History of the Life of St. Mesrop and of the Beginnings of Armenian Literature". These men, both of whom were disciples of Mesrop, bring to an end what may be called the Golden Age of Armenian literature. The Golden Age was to large extent a commentary and exegesis of Hebrew and Christian literary tradition and the history of the Armenian Apostolic Church.

Only a handful of fragments have survived from the most ancient Armenian literary tradition preceding the Christianization of Armenia in the early 4th century due to centuries of concerted effort by the Armenian Church to eradicate the "pagan tradition". Christian Armenian literature begins about 406 with the invention of the Armenian alphabet by Mesrop for the purpose of translating Biblical books into Armenian. Isaac, the Catholicos of Armenia, formed a school of translators who were sent to Edessa, Athens, Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch, Caesarea in Cappadocia, and elsewhere, to procure codices both in Syriac and Greek and translate them. From Syriac were made the first version of the New Testament, the version of Eusebius' History and his Life of Constantine (unless this be from the original Greek), the homilies of Aphraates, the Acts of Gurias and Samuna, the works of Ephrem Syrus (partly published in four volumes by the Mechitharists of Venice). In these first years of the 5th century were composed some of the apocryphal works which, like the Discourses attributed to St. Gregory and the History of Armenia said to have come from Agathangelus, are asserted to be the works of these and other well-known men. This early period of Armenian literature also produced many original compositions. Eznik of Kolb wrote a "Refutation of the Sects", and Koryun the "History of the Life of St. Mesrop and of the Beginnings of Armenian Literature". These men, both of whom were disciples of Mesrop, bring to an end what may be called the Golden Age of Armenian literature. The Golden Age was to large extent a commentary and exegesis of Hebrew and Christian literary tradition and the history of the Armenian Apostolic Church.

Music

The music of Armenia has its origins in the Armenian Highlands, where people traditionally sang popular folk songs. Armenia has a long musical tradition, that was primarily collected and developed by Komitas, a prominent priest and musicologist, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Armenian music has been presented internationally by composers Aram Khachaturian, Arno Babadjanian, duduk player Djivan Gasparyan, composer Ara Gevorgyan, producer DerHova, singers Sirusho, Eva Rivas and many others. Traditional Armenian folk music as well as Armenian church music is not based on the European tonal system but on a system of Tetrachords. The last note of one tetrachord also serves as the first note of the next tetrachord – which makes a lot of Armenian folk music more or less based on a theoretically endless scale. Armenians have had a long tradition of folk music from the antiquity. Under Soviet domination, Armenian folk music was taught in state-sponsored conservatoires. Instruments played include qamancha (similar to violin), kanun (dulcimer), dhol (double-headed hand drum, see davul), oud (lute), duduk, zurna, blul (ney), shvi and to a lesser degree saz. Other instruments are often used such as violin and clarinet. The duduk is Armenia's national instrument, and among its well-known performers are Margar Margarian, Levon Madoyan, Saro Danielian, Vatche Hovsepian, Gevorg Dabaghyan and Yeghish Manoukian, as well as Armenia's most famous duduk player, Djivan Gasparyan. Earlier in Armenian history, instruments like the kamancha were played by popular, travelling musicians called ashoughs. Sayat Nova, an 18th-century Ashough, is revered in Armenia. Performers such as Armenak Shahmuradian, Vagharshak Sahakian, Norayr Mnatsakanyan, Hovhannes Badalyan, Hayrik Muradyan, Raffi Hovhannisyan, Papin Poghosian, and Hamlet Gevorgyan have been famous in Armenia and are still acclaimed. The most notable female vocalists in the Armenian folk genre have been Araksia Gyulzadyan, Ophelia Hambardzumyan, Varduhi Khachatrian, Valya Samvelyan, Rima Saribekyan, Susanna Safarian, Manik Grigoryan, and Flora Martirosian.

The music of Armenia has its origins in the Armenian Highlands, where people traditionally sang popular folk songs. Armenia has a long musical tradition, that was primarily collected and developed by Komitas, a prominent priest and musicologist, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Armenian music has been presented internationally by composers Aram Khachaturian, Arno Babadjanian, duduk player Djivan Gasparyan, composer Ara Gevorgyan, producer DerHova, singers Sirusho, Eva Rivas and many others. Traditional Armenian folk music as well as Armenian church music is not based on the European tonal system but on a system of Tetrachords. The last note of one tetrachord also serves as the first note of the next tetrachord – which makes a lot of Armenian folk music more or less based on a theoretically endless scale. Armenians have had a long tradition of folk music from the antiquity. Under Soviet domination, Armenian folk music was taught in state-sponsored conservatoires. Instruments played include qamancha (similar to violin), kanun (dulcimer), dhol (double-headed hand drum, see davul), oud (lute), duduk, zurna, blul (ney), shvi and to a lesser degree saz. Other instruments are often used such as violin and clarinet. The duduk is Armenia's national instrument, and among its well-known performers are Margar Margarian, Levon Madoyan, Saro Danielian, Vatche Hovsepian, Gevorg Dabaghyan and Yeghish Manoukian, as well as Armenia's most famous duduk player, Djivan Gasparyan. Earlier in Armenian history, instruments like the kamancha were played by popular, travelling musicians called ashoughs. Sayat Nova, an 18th-century Ashough, is revered in Armenia. Performers such as Armenak Shahmuradian, Vagharshak Sahakian, Norayr Mnatsakanyan, Hovhannes Badalyan, Hayrik Muradyan, Raffi Hovhannisyan, Papin Poghosian, and Hamlet Gevorgyan have been famous in Armenia and are still acclaimed. The most notable female vocalists in the Armenian folk genre have been Araksia Gyulzadyan, Ophelia Hambardzumyan, Varduhi Khachatrian, Valya Samvelyan, Rima Saribekyan, Susanna Safarian, Manik Grigoryan, and Flora Martirosian.

Carpet

The term Armenian carpet designates, but is not limited to, tufted rugs or knotted carpets woven in Armenia or by Armenians from pre-Christian times to the present. It also includes a number of flat woven textiles. The term covers a large variety of types and sub-varieties. Due to their intrinsic fragility, almost nothing survives—neither carpets nor fragments—from antiquity until the late medieval period.

The term Armenian carpet designates, but is not limited to, tufted rugs or knotted carpets woven in Armenia or by Armenians from pre-Christian times to the present. It also includes a number of flat woven textiles. The term covers a large variety of types and sub-varieties. Due to their intrinsic fragility, almost nothing survives—neither carpets nor fragments—from antiquity until the late medieval period.

Traditionally, since ancient times the carpets were used in Armenia to cover floors, decorate interior walls, sofas, chairs, beds and tables. Up to present the carpets often serve as entrance veils, decoration for church altars and vestry. Starting to develop in Armenia as a part of everyday life, carpet weaving was a must in every Armenian family, with the Carpet making and rug making being almost women's occupation. Armenian carpets are unique "texts" composed of the ornaments where sacred symbols reflect the beliefs and religious notions of the ancient ancestors of the Armenians that reached us from the depth of centuries. The Armenian carpet and rug weavers preserved strictly the traditions. The imitation and presentation of one and the same ornament-ideogram in the unlimited number of the variations of styles and colors contain the basis for the creation of any new Armenian carpet. In this relation, the characteristic trait of Armenian carpets is the triumph of the variability of ornaments that is increased by the wide gamut of natural colors and tints.

Sinema

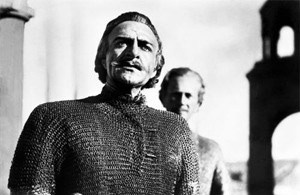

The cinema of Armenia was born on April 16, 1923, when the Armenian State Committee on Cinema was established by the government decree.

The cinema of Armenia was born on April 16, 1923, when the Armenian State Committee on Cinema was established by the government decree.

The first Armenian film with Armenian subject called "Haykakan Sinema" was produced in 1912 in Cairo by Armenian-Egyptian publisher Vahan Zartarian. The film was premiered in Cairo on March 13, 1913.

In March 1924, the first Armenian film studio: Armenfilm (Armenian: "Hayfilm," Russian:"Armenkino") was established in Yerevan, starting with Soviet Armenia (1924) Armenian documentary film.

Namus was the first Armenian silent black-and-white film (1925), directed by Hamo Beknazarian and based on a play of Alexander Shirvanzade describing the ill fate of two lovers, who were engaged by their families to each other since childhood, but because of violations of namus (a tradition of honor), the girl was married by her father to another person. The first sound film, Pepo was shot in 1935, director Hamo Beknazarian.

Armenian Art

- 2901